Nobody Asked Me, But… No. 267: Hotel History: Famous Artist Edward Hopper and His Hotel Management Paintings

The American artist Edward Hopper was known for interest in hotels, motels, tourist homes, and the wide scope of hospitality services. From 1920 through 1925 he worked as a commercial illustrator for Hotel Management and Tavern Topics from the Great Depression through the Cold War. He augmented his knowledge of hospitality services as a frequent guest in several lodgings on the long-distance automobile trips he took with his wife, the artist Josephine Hopper. Beginning in the mid-1920s and through the early 1960s, Hopper explored hospitality services subjects in paintings, watercolors, drawings, and prints. Sometimes he titled these works as “hotel” or “motel,” but just as often he did not. More than half are composites of sites, with no small amount of invention and artistic license.

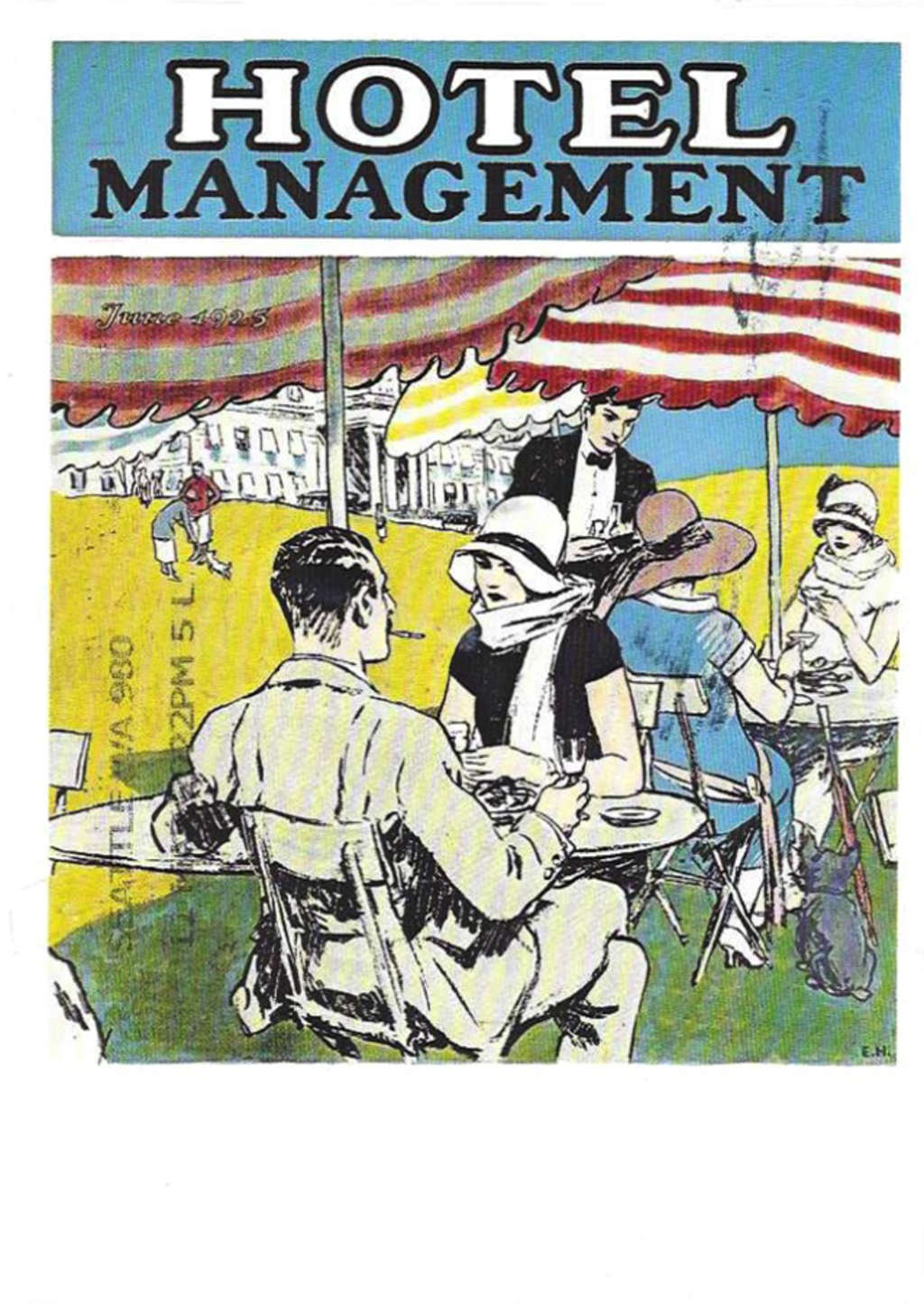

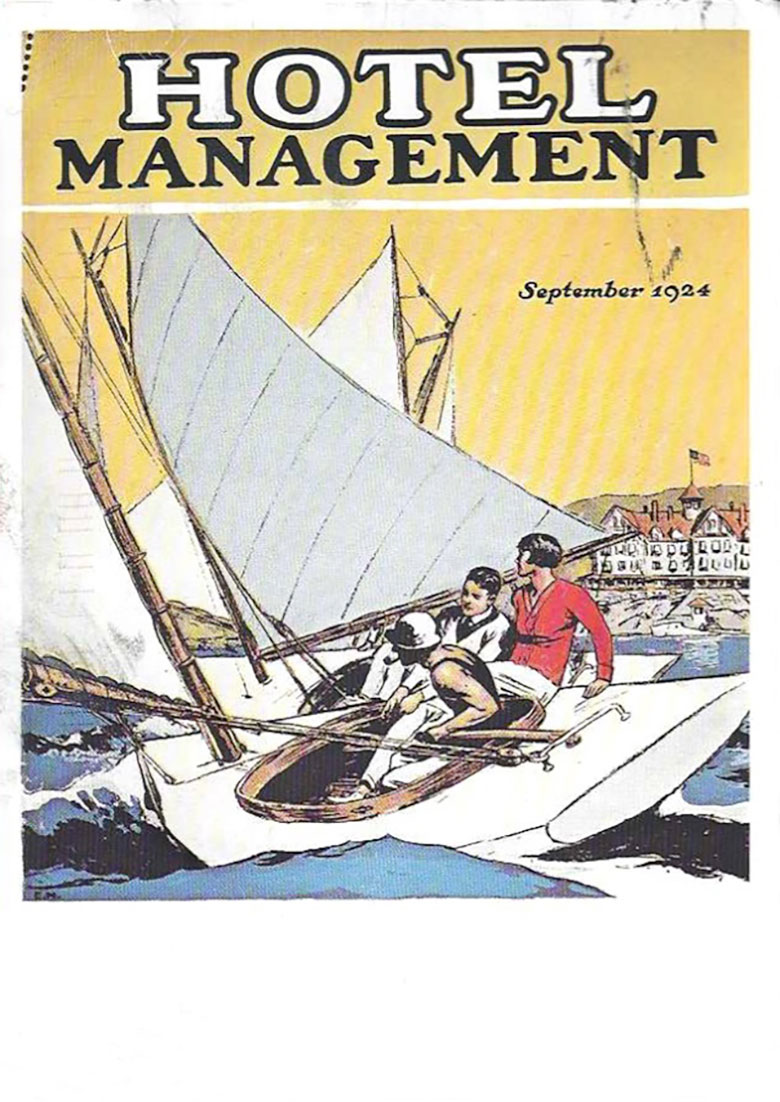

In the early 1920s, Hopper produced illustrations and covers for Tavern Topics, published and distributed by the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York, and in 1924 and 1925, he drew eighteen brilliantly illuminated covers for the trade magazine Hotel Management. Edward and Jo lived much of their lives in Manhattan, which, like other regions across the country, experienced a massive hotel-building boom in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Hotel-generated revenue fell by more than 25 percent in the Depression years of 1929 through 1935, which was hardly a deterrent to Hopper.

In the early 1920s, Hopper produced illustrations and covers for Tavern Topics, published and distributed by the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York, and in 1924 and 1925, he drew eighteen brilliantly illuminated covers for the trade magazine Hotel Management. Edward and Jo lived much of their lives in Manhattan, which, like other regions across the country, experienced a massive hotel-building boom in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Hotel-generated revenue fell by more than 25 percent in the Depression years of 1929 through 1935, which was hardly a deterrent to Hopper.

Between the World Wars, Hopper produced at least two etchings and five paintings synthesizing architectural components of various urban hotels—some of which he knew from living in New York, while others harked back to images suggested in the pages of Hotel Management during the years he produced its covers. For the most part, the covers depict elegant couples dancing, dining and boating in a hotel environment.

Looking out from the vantage point of their home at 3 Washington Square North in New York, the Hoppers would have encountered several hybrid rental structures, including a ten-story campanile at 53 Washington Square South. Designed by McKim, Mead & White and built in 1893, this was actually part of the Hotel Judson, the proceeds from which benefitted the colonnaded Judson Memorial Church next door. Hopper captured this view in the painting November, Washington Square, which he commenced in 1932 and to which he added sky components in 1959. The Hoppers’ friend, artist John Sloan, lived at the Hotel Judson for eight years, until he was evicted by New York University (which had earlier annexed the property). The three-story, burnt orange structure at far left in the painted version is the House of Genius boardinghouse, at 61 Washington Square South, which, at various times from the 1910s through the 1930s, housed artists, authors, poets, and musicians, including Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Eugene O’Neill, and Alan Seeger.

Apartment hotels are among the structures figuring in the architectural types Hopper synthesized in selected compositions such as House at Dusk. Popular, urban lodging houses offering short-term leases, these were essentially apartments but with the amenities of a hotel. These middle-class hybrid spaces contained multiple units with shared bathrooms and frequently contained sitting rooms with pianos and offered a restaurant, a doorman, and daily maid service.

Apartment hotels are among the structures figuring in the architectural types Hopper synthesized in selected compositions such as House at Dusk. Popular, urban lodging houses offering short-term leases, these were essentially apartments but with the amenities of a hotel. These middle-class hybrid spaces contained multiple units with shared bathrooms and frequently contained sitting rooms with pianos and offered a restaurant, a doorman, and daily maid service.

The result of at least nine study drawings, Hotel Lobby is probably Hopper’s most comprehensive treatment of the hospitality services theme. Seated in an upholstered chair, a young woman in a blue dress reads her book, reclining at angles that mirror those of her more mature counterpart across the foyer. On the back wall, a view through dark drapes in an open doorway reveals a restaurant with linen-covered tables. The lines formed on the floor reflect period design principles treating carpet as a means to guide crowds and determine the placement of furniture. Even more important for crowd and climate control is the revolving door—cropped at left in Hotel Lobby. For all Hopper’s urban architectural imagery, revolving doors appear in just two of the studies for this work and in only one other painting (Sunlight in a Cafeteria, 1958, in the Yale University Art Gallery). Variations of the revolving door had existed since at least the mid-nineteenth century with the quest to regulate ventilation and keep temperatures constant in public settings. Allowing no air in from the outside, a revolving door was, in the words of an early promoter, “always closed.” This helps explain how Hotel Lobby, a painting finished in January of 1943, and featuring a couple in winter clothing, could also depict a coatless woman in a short-sleeve dress.

Many of the 18 known Hopper HM front covers were done in the mid-1920s. For the most part, the covers depict one or more elegant couples enjoying an activity such as dancing, dining and boat set against a created hotel background. Hopper used actual hotels—Ohio’s Cincinnatian Hotel and New York’s Mohonk Mountain House—as inspiration on two of the covers. The illustrations’ light colors and energetic activities are a distinct departure from Hopper’s more-somber famous works, such as “Automat” or the iconic “Nighthawks”. The Hoppers, Edward and Josephine [also a painter], had lunch every day at The Hotel Dixie in New York.

Many of the 18 known Hopper HM front covers were done in the mid-1920s. For the most part, the covers depict one or more elegant couples enjoying an activity such as dancing, dining and boat set against a created hotel background. Hopper used actual hotels—Ohio’s Cincinnatian Hotel and New York’s Mohonk Mountain House—as inspiration on two of the covers. The illustrations’ light colors and energetic activities are a distinct departure from Hopper’s more-somber famous works, such as “Automat” or the iconic “Nighthawks”. The Hoppers, Edward and Josephine [also a painter], had lunch every day at The Hotel Dixie in New York.

And perhaps absorbing the hospitality mindset that it’s all about the guest experience, the VMFA has gone one step farther, recreating the hotel room seen in Hopper’s 1957 work “Western Hotel.”

Edward and Jo began renting summer cottages in South Truro on Cape Cod in 1930 and would buy property and then build a home there a few years later. By the 1940s, Cape Cod possessed a number of tourist homes—furnished single-family dwellings offering rooms for short-term stays, often seasonally. Deeply interested in domestic architecture, Hopper painted several tourist homes over his long career, but he seems in retrospect to have been particularly interested in one such residence in Provincetown on Cape Cod. He spent several long nights parked before the structure, making drawings, resulting in a painting that offers a view into the front rooms of the house—apparently, the inhabitants wondered what the artist was doing, sitting there in his Buick sketching away.

The Hoppers took long periodic road trips in search of subject matter across New England, the West, and Mexico, among other locales. On these jaunts, they stayed at tourist homes and, eventually, as Edward’s income increased, in motels and motor courts. Portions of Jo’s diaries—covering the mid-1930s to the 1960s, and recently given to the Provincetown Art Association and Museum—reveal page after page of extended descriptions of these lodgings and the couple’s feelings about them. One of the more colorful and lengthier of these entries discusses their stay at the Weseman Motor Court in El Paso from December 15 through December 22, 1952. Hopper painted Western Motel during a fellowship at the Huntington Hartford Foundation in Pacific Palisades, California, but the canvas also evokes Jo’s descriptions of and contemporary press discussing lodgings in El Paso.

The Hoppers took five long trips to Mexico between 1943 and 1955, on which they also visited several regions in the United States; they traveled by train in 1943, but on the other jaunts they traveled by car. They frequently sized up a locale based on the quality of their lodgings and the view offered by their room and from the structure’s roof. Much of what we know about Hopper’s time in Mexico comes from the couple’s correspondence on hotel and motel letterhead and postcards. Dating from his first trip to Mexico, Saltillo Rooftops enlists the stovepipe of his hotel rooftop at the Guarhado House (where he and Jo stayed) in the foreground to balance the unfolding span of the Sierra Madre mountains in the background. In Monterrey Cathedral, he returns to his practice of using his lodgings (in this case the Hotel Monterrey) as a framing device to synthesize a visual inventory of hotels and other structures—the cropped signage for the Hotel Bermuda appears at the lower left. Hotels and motels may provide a useful metaphor for understanding much of Hopper’s work in general. He took for granted that hotels and paintings offer temporary experiences, serve multiple individuals, and are, ultimately, highly crafted illusions. Hopper viewed his art—his paintings and watercolors in particular—as sites in which to invest temporarily and upon which to muse later with equal parts introspection and nostalgia. Sixty-nine of these paintings, watercolors, drawings, prints, and magazine covers are featured—along with thirty-five works on the theme by other artists—in the exhibition Edward Hopper and the American Hotel at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond.

It is perhaps fitting that the exhibition is organized by and makes its debut there. The Hoppers visited Richmond on several occasions. His own art would be featured in subsequent biennial exhibitions. Hopper returned to the museum in 1953 for a Judge the Jury exhibition, around the time the museum purchased House at Dusk. A photograph from this visit shows Hopper and Richmond artist Bell Worsham standing before Hopper’s painting Early Sunday Morning. Following up on some spirited communication, via the couple’s lodgings on this visit, the museum’s director, Leslie Cheek Jr., assured Hopper, “While in Richmond you will be quartered at the Jefferson Hotel, a Beaux-Arts structure I believe you will enjoy.” There were plenty of hotels in which Cheek could have placed Hopper, but he made sure that the artist was staying at an establishment recognized as the “finest in the South.”

Hopper’s work for Hotel Management did indeed, influence his career. The things he did for Hotel Management—and even some of the photographs and advertisements and articles—provided a storehouse of images and ideas he would return to again and again.

All of my following books can be ordered from AuthorHouse by visiting stanleyturkel.com and clicking on the book’s title:

- Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2009)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels in New York (2011)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels East of the Mississippi (2013)

- Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt, Oscar of the Waldorf (2014)

- Great American Hoteliers Volume 2: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry (2016)

- Built To Last: 100+ Year-Old Hotels West of the Mississippi (2017)

- Hotel Mavens Volume 2: Henry Morrison Flagler, Henry Bradley Plant, Carl Graham Fisher (2018)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume I (2019)

- Hotel Mavens: Volume 3: Bob and Larry Tisch, Curt Strand, Ralph Hitz, Cesar Ritz, Raymond Orteig (2020)

- Great American Hotel Architects Volume 2 (2020)

If You Need an Expert Witness:

Stanley Turkel has served as an expert witness in more than 42 hotel-related cases. His extensive hotel operating experience is beneficial in cases involving:

- slip and fall accidents

- wrongful deaths

- fire and carbon monoxide injuries

- hotel security issues

- dram shop requirements

- hurricane damage and/or business interruption cases

Feel free to call him at no charge on 917-628-8549 to discuss any hotel-related expert witness assignment.

Stanley MHS, ISHC Turkel

+1 917 628 8549

Stanley Turkel, MHS, ISHC