ESG in hotel real estate: Green financing and what it means

The ‘pandemic awakening’ has brought forth numerous discussions, ranging from the incessant remote working debate to tackling an impending economic crisis. However, as the threat of irreversible climate impacts continue to loom over our heads, none have resounded in a manner quite like the growing calls for firmer action towards environmental sustainability. If ESG in hotel real estate is to be implemented in a credible and effective way, it demands a deep understanding of what green financing means and the possibilities it can lead to.

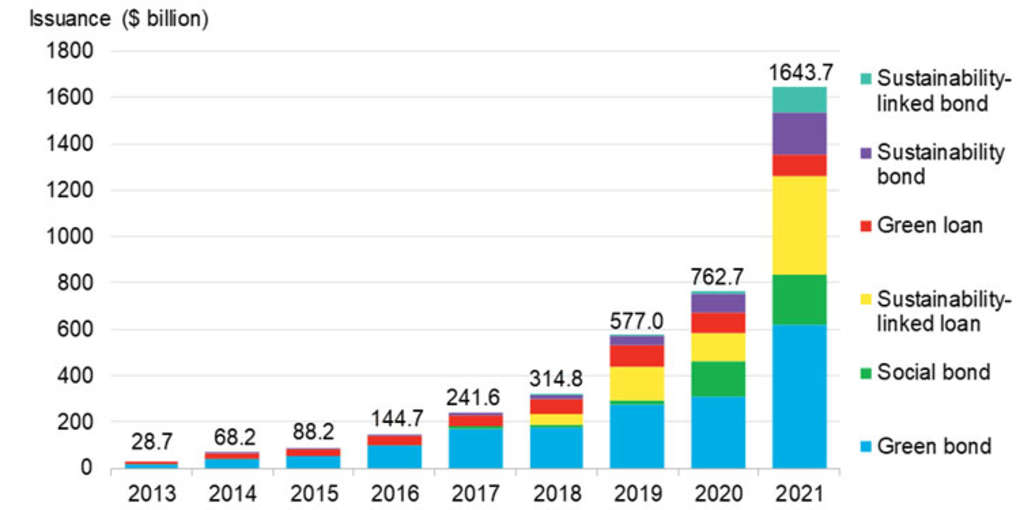

As the mammoth engine underlying our economy, the financial sector wields immense power that could either make it the chief help or chief hindrance towards this goal. And let’s be clear – when the star player decides to set its feet on the field, the results are apparent: In 2021 alone, sustainable debt issuance exceeded US$1.6 trillion, more than doubling the already-record volume achieved in 2020, signalling a marked inflow of capital and undeniable push towards sustainable activities.

Green hotel financing and why it matters

In hotel real estate, promising signs of a shift towards greener capital began to emerge in 2019, when BBVA and Pestana Hotel Group issued the world’s first hotel green bond (€60 million), while Host Hotels & Resorts soon after became the first U.S. Hospitality REIT to issue a green bond (US$650 million).

Since then, hotel green loans too have been on an upward trajectory, secured by firms like the Edwardian Hotels London towards financing the development of The Londoner (£175 million), as well as Singapore-based Park Hotel Group to refinance the Grand Park City Hall in Singapore (S$237 million). In 2022, Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Project closed a green facility amounting to a colossal SAR14.12 billion (US$3.8 billion) to develop 16 hotels in the Kingdom, setting a new pace in the global movement towards sustainable development.

The importance of this all? With senior lenders typically financing over 50% of a hotel asset’s market value and some debt funds even pushing the 85% mark, financing is certainly a key slice of the hotel investment pie, and the availability and cost of debt can very well switch the green light off or on for many investment decisions. Therefore, green financing, if used appropriately by its stakeholders, can be an important driver for sustainability in the sector. But what does the term really entail?

Defining ‘green’

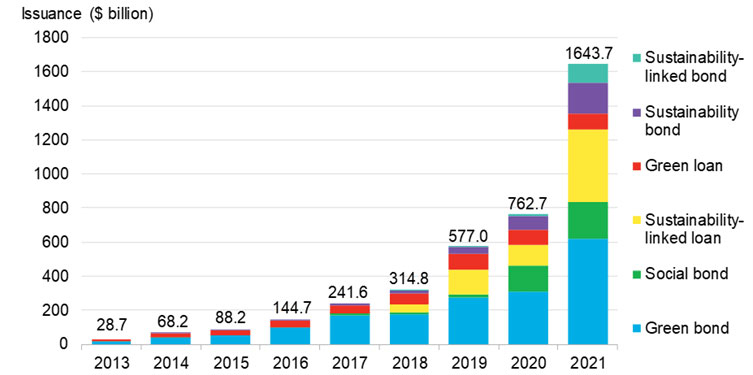

First off, let’s talk about what being ‘green’ means in the lending economy. In this respect, there are two sides to the balancing scale: the first being the lenders’ sources of capital (inflow), and the second being how they lend on green financings (outflow).

Green capital and where it flows from

Surprise, surprise, in case you didn’t realize, lenders get their money from somewhere – whether from investors who invest into debt funds expecting a certain level of return, or by refinancing themselves through other financial instruments such as issuing bonds, commercial papers (CPs), or from different forms of banking deposits.

These sources of capital can be explicitly ‘greened’ through the establishment of green debt funds or the issuance of debt securities such as green bonds, whereby capital is raised specifically to fund green projects – and most, if not all of their proceeds must be used as such. Green debt funds active in the hotel space, as well as lender-issued green bonds meant specifically for financing hotels remain few and far between – if existent at all – especially as the sector remains relatively niche.

Nevertheless, a green financing does not necessarily have to be funded from a green source of capital. The issuance of green bonds, for example, is one way to demonstrate commitment to sustainability, to be in line with corporate strategies and regulations, as the use of its proceeds are thereby limited to green projects. However, general (real estate-focused) debt funds and bonds can also be used to fund green hotel financings, as long as the financing qualifies as ‘green’.

What makes financing green?

At present, there is no standard definition of a ‘green financing’. Each lender may have different frameworks and considerations, such as Aareal Bank’s Green Finance Framework, BNP Paribas’ Green Bond Framework, and UOB’s Sustainable Bond Framework – although their underlying principles remain similar, and are typically aligned with globally-recognized guidelines such as the International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) Green Bond Principles and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs).

Varying regulatory requirements across jurisdictions also make it challenging to find a single, universal method of qualification. In real estate for example, a building with an ‘A’-rated energy performance certificate in one country may receive a ‘B’ grade in another, due to different assessment standards. Qualification methods should therefore be internationally intelligible.

Accordingly, common ways of qualifying a green real estate financing currently include: (i) international green certifications such as BREEAM or LEED; (ii) meeting set thresholds on energy efficiency or carbon emission levels; or (iii) certified compliance with regulations.

The specifics of structuring a green hotel financing differ vastly from loan to loan (depending on market, asset quality etc.) as well as between lenders. For example, some lenders may tend towards providing standard green loans that may or may not include financial benefits, while others may offer a more layered ‘sustainability-linked loan’, which incentivizes the borrower to meet certain pre-agreed targets through margin reductions.

To green or not to green? Challenges and opportunities

Hotels are typically perceived as a ‘risky asset class’; the unstable cousin of the traditional real estate asset classes of offices, retail and logistics. Their crime? Having an operational focus, playing host to many short-term ‘tenants’ (i.e. hotel guests) that generate fluctuating cash flows, rather than long-term occupiers offering a secure pay check. On top of which, the transient nature of travel and tourism gives hotels an inherently bad rap in the environmental department (single-use plastics, frequent linen changes etc.). In other words, hotels aren’t necessarily the most obvious candidate for green financings.

However, hotel assets built with sustainability in mind can equally qualify for green financing through green construction certifications. Meanwhile operationally, hotels could in fact benefit from having a single operator who has greater control over the building’s emission and consumption patterns (instead of juggling multiple office or retail tenants), as well as hold more opportunities, for example, implementing energy-saving initiatives or reuse resources.

Additionally, hotels are a diversified asset class that does not shy away from ‘off-the-beaten-track’ locations and often seeks to integrate into local communities, whilst typically having a larger and more diverse workforce. This gives them the opportunity to contribute to local employment, biodiversity, etc. that could hit the ‘S’ mark in ESG.

Therefore, the hotel sector is no less fit for green financing than its ‘traditional’ counterparts – rather, its operational layer may simply bring different considerations to how this green label can be earned. That said, green hotel assets are still relatively scarce in the market today, with qualifying assets typically being new builds or recent renovations. In fact, the very nature of (operational) real estate means that building anew or making retrofits to ensure compliance will take significant time and/or capital expenditures – which means that unsurprisingly, the race to sustainability in the sector is much more a marathon than a sprint.

So, what’s the deal with green financing?

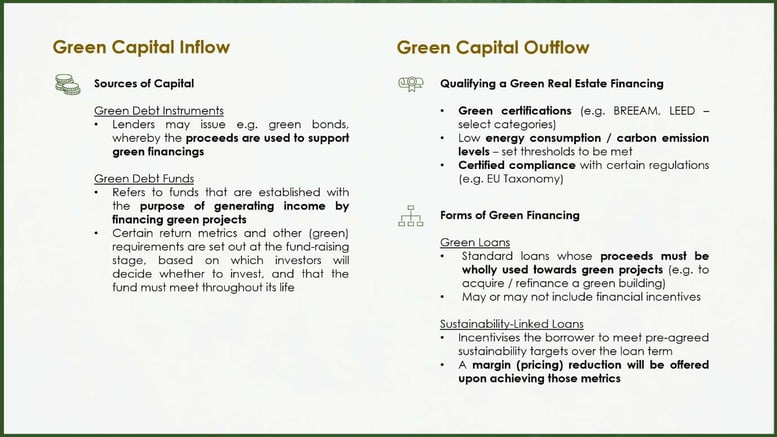

The ESG frenzy has been taking front and centre stage across industries and markets, and had initially set the eyes of many investors on the prospect of cheaper debt through green financing. The prevailing conception was that green or sustainability-linked loans should come at a lower cost, such that eligible investments or capital expenditures could carry an overall net benefit, or at the very minimum, incur less losses.

In theory, this ‘greenium’ (i.e. green premium) phenomenon may be seen through both explicit benefits offered by lenders as well as implicit asset advantages, as outlined in some examples below.

The reality, however, is that explicit pricing adjustments by sole virtue of a loan being ‘green’ currently remain limited in hotel real estate. Data availability and transparency or the lack thereof, continue to plague the fight for sustainability, as it is difficult for both investors and lenders to assess and quantify an asset’s exposure to climate risk, thereby making it equally difficult to factor into a financing.

What’s in a price tag?

Apart from hawk-eyed loan-to-own seekers, lenders are primarily concerned with a borrower’s ability to service and repay their debt, against which there are several risks that may hinder this goal. One key consideration is a loan’s ‘refinancing risk’ – as the loan matures, the asset should be able to be refinanced by another lender, such that the existing lender can be fully repaid.

With rising climate risk, some assets are increasingly in danger of becoming ‘stranded’, whereby the asset experiences unexpected write-downs, devaluations, or require significant capital expenditures due to external shocks. For example, a hotel could be so far removed from its required net-zero carbon pathway that compliance becomes an impossible target. This could lead to significant refinancing risk as third-party lenders may not want or even be able to refinance the asset at maturity. Non-compliance could also mean discounts on value, which further exacerbates the refinancing risk by putting a ceiling on the loan quantum it can obtain.

As ESG becomes more mandatory than voluntary and such adverse scenarios become a real possibility, there is in fact the sentiment that rather than compliant assets necessarily benefitting from a purported ‘greenium’, we may soon see ‘brown discount’ penalties on non-compliant assets. Because unsurprisingly, the higher the risk, the higher the price – if financing can even be obtained at all.

More than just a number

As regulators begin to double-down and reporting deadlines draw nearer, many investors themselves are being bound not only by increasing regulations and corporate social responsibility to grow their green portfolios, but also the rising exit risk of their investments, as non-compliance could severely limit an asset’s investor pool and its ability to obtain financing. Green financing is therefore fast becoming more a necessity than an opportunity to find cheaper debt, and investors are starting to seek out that green financing stamp even if no pricing benefit can be offered.

Where do we go from here?

As we saw at the beginning of this article, exponential nominal growth has hit the ESG debt market in the past year. But let’s put things into perspective: according to the Institute of International Finance (IIF), ESG debt still in fact only accounts for a meagre 1% of global debt. Which is perhaps a fairly accurate reflection of where sustainability stands in the market today – awareness has exploded, progress has been made, but in terms of real impact made? Probably a ripple in the ocean.

Granted, Rome was not built in a day. Tools and procedures have to be devised, implemented, and then perfected. And as the donkeywork continues, there is one ingredient that will stand pivotal: data.

Data, data, data

Climate risk is generally defined in two broad categories: physical risk (due to changes in weather patterns) and transition risk (as economies seek to decarbonize). While physical risks tend to be more apparent (e.g. a coastal resort is more susceptible to rising sea levels), transition risks are more dependent on human intervention (changes in regulatory requirements, investor expectations etc.) and require closer, more data-driven monitoring.

Access to reliable data is the cornerstone to managing transition risks, serving three crucial aims: (i) for underwriting and due diligence purposes to invest/lend into the right assets; (ii) ongoing monitoring and reporting; and (iii) identifying areas for green initiatives.

Rising regulations, a necessary catalyst to ensuring that the right steps are being taken at the right time, are soon expected to shake up the status quo. This includes new climate disclosure requirements announced by the European Banking Authority in 2022 that will require EU banks to disclose their exposure to carbon-intensive activities and assets that are subject to climate risk, amongst other requirements by 2023 and 2024. Accordingly, existing borrowers and those seeking financing will be required to provide energy performance certificates, carbon emissions data and the like, as well as adhere to ongoing data reporting requirements.

Through the reality glass

As the need for quality and timely ESG reporting increases, this would create a greater availability of and accessibility to data. Consequently, this could enable a dawn of more ESG-focused metrics in the underwriting and due diligence processes, including more quantitative assessments from valuers on an asset’s state of compliance, together with possible impacts on valuation. This would mean greater overall transparency, which would have a significant influence on the lending environment and pricing considerations.

Eventually, this could also lead to the normalization of using ESG assessment metrics, such that ESG considerations become the rule rather than the exception – which means, ‘carbon emissions per available room’ soon becoming a common discussion may not be too far off reality.

Driving change: Key stakeholders and the perils of green paper chasing

The pace of evolution towards an environmentally-friendly climate and the quality of impacts largely depend on the stakeholders – how they perceive the issue and their commitment towards the cause. Evidently, we’ve got the awareness part down. But the trouble with fame is that everyone wants to be your friend; ESG is the new Vogue, and ‘green’ is valuable as gold. And like a double-edged sword, that signals greater efforts and resources to be channelled to environmental protection – as well as the counterproductive consequences of greenwashing.

Technical experts and consultants in particular have a strong duty to provide reliable data and actionable advisory, while certification processes must remain stringent and comprehensive, especially as dependence on such expertise will only continue to increase. Similarly, investors/borrowers and lenders should look beyond simply growing their green portfolio figures, while operators too should walk the talk in implementing effective measures that go beyond just what the guest sees.

Regulations will continue to play a firm role in setting the tone for sustainability, but the real movers and shakers are the ones executing the deed. Above all, accountability should be the chain binding each stakeholder, especially as we live in an economy obsessed with corporate image and compulsive monetization – and every misstep is an expense against the environment.

The road ahead

There are two arguments for the green debate: one practical, the other moral. From a practical point of view, with rising regulations and public scrutiny on reaching global environmental targets, the climate risk that could influence an asset’s value is becoming a very real consideration for both investors and lenders. Financial leverage is a key driver behind many investment decisions, meaning that as lenders tighten lending requirements in accordance with increasing regulations, (potential) borrowers will no longer be able to sit back and relax. In fact, as the race towards carbon neutrality intensifies, future proofing assets will more likely mean protecting value than necessarily capturing ‘greenium’ value.

Meanwhile, the moral perspective is far less a question than it is simply an obligation, especially seeing the extreme climate events of late. Put bluntly in fact, perhaps the greatest fallacy is in believing that money is to be made from helping an environment that we have categorically destroyed. And the environment is just one-third of the ESG equation. Mindsets may have changed rapidly over the past year, but the truth is that in terms of execution, taming the ‘E’ remains particularly time-critical yet largely unchartered territory that many are still figuring out.

ESG as a whole needs to become second nature to our economy, with real impacts being made from a culmination of awareness, commitment, and expertise. Because clearly, the awareness flag alone will not hold on the tip of a melting iceberg.

EHL Hospitality Business School

Communications Department

+41 21 785 1354

EHL