50 Shades Of Chatbots: What Remains After The Sexiness Has Gone

REBIRTH: AN INTRODUCTION

A few days ago, during a casual conversation on the state of AI in our industry, a friend told me: "You know what? Now that chatbots are no longer sexy, they are finally becoming useful". It is a rather bold statement but, at a closer look, it also happens to be quite accurate. Over the last year, in fact, concepts such as the Gartner's cycle, the tech adoption lifecycle or the dot-com crash analogy have been heavily quoted in articles and studies on chatbot technology. And, usually, when such (overused) concepts start popping up in blogs and publications, we're past the hype. Way past it.

"Now that chatbots are no longer sexy, they are finally becoming useful"

The dot-com bubble analogy, especially, is so obvious that sounds almost trite, yet it's undeniable that, once the web lost its "tech sexiness" in the early '00s, it started flourishing and molding into what it is today. Like the legendary phoenix, it rose from its own ashes, and it's not so far fetched to presume that story will repeat itself with chatbots.

CHATBOTS ARE BABY BOOMERS, NOT ALPHA GENS

So, the fact that bots are the Next-Big-Thing no more is not necessarily a bad thing. Quite the contrary. Keeping a low profile will likely make them adapt and evolve to accomplish their original mission: helping the end-users, rather than keeping investors' inflated expectations high. Tech-Darwinian natural selection, you may call it, even though part of the industry is not so optimistic about bots' future. Christopher Elliott, a contributor at Forbes, recently ran the extra mile by saying that "chatbots are killing customer service". This is, by far, an overstatement, but the harsh truth is that, at least up until now, few (if any) companies have been able to deliver a genuinely frictionless chatbot experience. Most businesses seemed to be more driven by the fear-of-missing-out the bot-wagon rather than by the will to serve their customers.

"Up until now, no company has been able to deliver a genuinely frictionless chatbot experience"

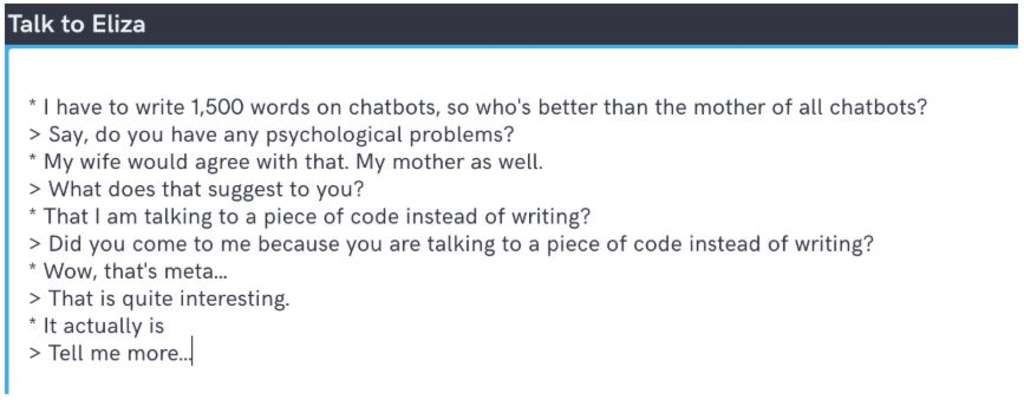

That being said, this FOMO should have turned into terror by now: chatbots, in fact, are not at all that brand new, disruptive technology we are lead to think. The earliest incarnations of NLP programs are over half-a-century old. You have an example of it in the first image of this piece. "Even if the technology is old", Aldo Polledro, CEO and Founder of TellTheHotel told me, "it needs to be improved and adapted to new possibilities and user scenarios. Today", he continues, "the industry and the value proposition are not clearly defined, but in 5 years time that wouldn't be the case anymore".

"Today, the industry and the value proposition are not clearly defined, but in 5 years time that wouldn't be the case anymore"

LAZINESS AND DECISION-TREE LOGIC

American science-fiction author Robert Anson Heinlein once wrote that "progress isn't made by early risers", but rather by "lazy men trying to find easier ways to do something". I agree. And, when it comes to bots, I cannot really find a more fitting description. Problem is that, quite often, "these lazy men" have no idea what they are trying to solve. Chatbot is a vague concept to the man in the street, a vagueness that most bot' greedy companies exploited. The vast majority of chatbots today are simply based on decision-tree logic, so there's no real AI involved. Authentic learning capabilities are still the exception, rather than the norm. In a nutshell: most intelligent assistants are far from intelligent. Duh! Don't get me wrong, there is nothing intrinsically incorrect with flow-based bots: a decision tree, in fact, plays a key role in guiding users, especially during the first interactions with the bot. Without this crucial guidance, there's a high risk of getting a multitude of questions, poorly written and out of context. Investing in Machine Learning too early, paradoxically, can be not only useless, but a total waste of money. "Any chatbot company should probably start with simple heuristics, regular expressions, pattern-matching and rule-based", told me Chris Gerpheide, VP of Engineering at Bespoke, "and, even before that, humans, as they can learn quickly about what your customers actually need. In my opinion people make too big a deal out the AI aspect of chatbots, when ultimately all that matters is if you can give the user what they want".

"People make too big a deal out the AI aspect of chatbots, when ultimately all that matters is if you can give the user what they want"

Moving from heuristics to machine learning is, in fact, an incremental improvement process, and you need data to train" the bot in either case: a simple machine learning algorithm might do something like breaking a sentence up into words and then train the algorithm with their combinations. This improvement would give you better flexibility in word order than strict pattern-matching, but you could make this word-order-independent optimization and still just use heuristics rather than real machine learning. Similarly, you could do things like compare against synonyms of words (e.g. "town" and "city"), further reducing the amount of data needed for training, in either a heuristic or a machine-learning context. "A simple example", Gerpheide continues, "is taking two user queries, such as "is there early check-out?" and "when is check-out time?". We could either treat these as two separate questions with distinct answers, or catch them in one intent and give a response that covers both. That decision could significantly change the likelihood of us giving the user the information they want, but has more to do with the conversation design than the algorithm. The challenge is measuring and improving the performance of our algorithms independently of the data".

Problem with decision-tree-only logic chabots is that they heavily rely on the ability of their developers to anticipate all the possible questions users may ask. To put it simply: they need humans' help.

"There is nothing intrinsically wrong with flow-based bots, but they heavily rely on the capabilities of their developers to anticipate all the possible questions users may ask"

According to BeSpoke CEO, Akemi Tsunagawa, this has been the case for her company too. "In the early days", she confided me, "we had human operators answering questions too, just in case the bot failed to answer. Now that we have large enough user base and data sets, answers to key queries are automated without human involvement". It is an interesting way of looking at the issue, and it proves that obstacles must be overcome not only during the development of the technology, but also (and, I would add, more importantly) after the technology is launched. "Building a bot that works is one thing", continues Tsunagawa, "but getting people to use it is another. And getting the same user continue to chat is even harder. It's almost like running A/B tests on a website: at the end, the only thing that matters is the content".

WHERE GOOD BOTS GO TO DIE

According to David Curran, Machine Learning Engineer at OpenJaw Technologies, one of the main difficulties is that, in order to develop a good bot, many different (and, often, rival) departments have to work together and look at the project from different angles. In his book The Wisdom of Crowds, author James Surowiecki wrote that "homogeneous groups are great at doing what they do well, but they become progressively less able to investigate alternatives". More often than not, in fact, chatbots fail due to the inability of the management to combine their employees' diverse expertises in the right, harmonic way. Think about the bot's tone-of-voice, for example: "This is not an area IT understands", Curran told me, "but marketing people do, and bringing them into product development makes all the difference in the world. Programmers", he continued, "think everything can be programmed, but what bots really need is to be trained. You can always tell if a chatbot has been created by IT people alone, as it lacks all the various nuances of human-to-human conversation".

"You can always tell if a chatbot has been created by IT people alone, as it lacks all the various nuances of human-to-human conversation"

THE COMPANY'S WORST JOB: HERA AND THE RES-BOT

"HERA is your best employee competing for the company's worst job". I love this quote by Brendan May, Managing Director at Hotel Res Bot, as it sums up perfectly what a robot is (or, at least, should be) all about. The acronym HERA stands for Hotel Email Reservation Assistant, and it is, at its core, a system that scans your inbox and automatically sends tailor-made offers to your guests. I gave him a call to discuss this fascinating concept. "First of all", May corrects me right away, "HERA is not a chatbot. And it's not an IT either. She's a SHE. We like to think of HERA as a virtual reservation agent. You may call her a resbot". The idea tickled my curiosity and I tried to get a grasp on the system: once the hotel booking department receives an email, HERA automatically runs an intent analysis. Thanks to it, HERA understands if the message comes from a potential customer or simply from a checked-out guest who forgot his wallet in the room. Once HERA understood that the intention behind the text is to, let's say, reserve, it connects to the hotel's ARI and sends the potential booker a proposal, based on his original request. "Ok", I played dumb, "but how it, I mean... SHE, is not a chatbot?". "A chatbot", May replied, "is merely a serialized contact form, that's why talking to one always feels so unnatural. What HERA does is different. There's no back-and-forth, she tries to answer customers' request in full and, if she can't, she passes them to a human being. And by simply doing that, she is already simplifying a process".

"HERA is your best employee competing for the company's worst job"

THE "US vs. THEM" BIAS

While talking to May, he touched an issue that I always felt central in the bot-vs-human diatribe: "A lot of companies", he said, "thrive on adding layers of complexity to their products and services. But, when it comes to bots, the question is quite banal: is that really necessary? I mean, if a bot is helping humans getting rid of repetitive, boring tasks, then fine. Otherwise, just drop it".

"If a bot is helping humans getting rid of repetitive, boring tasks, then fine. Otherwise, just drop it"

In one of the best pieces I've read on AI in hospitality (https://www.phocuswire.com/Human-touch-AI-hotels), Avvio's CEO Frank Reeves wrote that "replacing human interaction where it does not add any value, and increasing it where it does, is the optimum use of AI". And that's where a lot of companies get it wrong. If a chatbot is not "competing" in order to replace a human (remember? The worst job?), then it's probably going to be useless anyway.

THE NEW WAVE OF BOTS

Accor and Paris Aeroports recently participated in a $10 million Series A fundraising for Mindsay, a French chatbot company including, amongst its customers, names such as Disneyland Paris, Vueling, Iberia, and SNCF. According to Mindsay, Iberia's bot "sold" its first plane ticket. Impressive. I got in touch with the company's CEO, Guillaume Laporte, who commented on the story: "The success of Iberia proves that vertical bots have the highest ROI for companies", he told me, "both in terms of customer support optimization and pure conversion. These two", he continues, "are the main KPIs monitored by companies when adopting a bot". And, according to Laporte, Mindsay can reduce the human support agents' workload by an average of 30% and increase conversion rate by up to five points.

"The success of Iberia proves that vertical bots have the highest ROI for companies"

Mirko Lalli, CEO & Founder of Travel Appeal, is equally optimistic: "Successfully utilizing mobile messaging allows for organizations to build loyalty, improve review scores and greatly enhance the overall guest experience", he told me. Conversation, Travel Appeal's chatbot, has been adopted by Best Western Italy under the name Best Friend, and it provides guests with details about their booking or general information about the hotel, together with self-check-in, up/cross-selling, satisfaction surveys and a facilitated booking system. "By combining past interactions and APIs", Lalli continues, "our specialists can train the chatbot to understand the meaning of various questions and respond appropriately. The technology's backbones are founded on a Machine Learning system that learns and improves over time, hyper-personalizing the guest experience".

"The goal is not to have a conversation just like a human would, but rather to help the users in the best possible way", says Tiago Araújo, Co-Founder of HiJiffy. Again, during the interview, I had the impression that the main constant in good bots seems to be the quality and quantity of historical data. "Focusing on hotels has allowed us to have a base of hundreds of thousands of conversations within the same topics, that are used to power our chatbot and make it smarter with each passing day", Araújo continues, highlighting how a vertical, hyper-specialized approach is also essential: "specialization is fundamental: a chatbot must have very well delineated use cases and not try to do a little of everything, the necessary learning to enable that can rapidly increase to the millions of interactions and very few companies have that level of volume". Results are impressive: according to Araújo, in fact, HiJiffy handles up to 70% of conversations without any kind of human intervention.

"The goal is not to have a conversation just like a human would, but rather to help the users in the best possible way"

SIMPLY ELEGANT: CONCLUSION

So, what remains of chatbots after the sexiness is gone? Quite a lot, apparently. I discussed it with Stephen Burke, SVP Travel & Hospitality at Sciant, an IT consultancy and software development company with customers and partners all around the world. "A chatbot is just another user interface", he stated, "sometimes elegant, sometimes quite complex". When I showed him the first draft of the piece you're currently reading, he immediately pointed at Curran's quote on chatbots made by IT people: "I would take it a step further: not only should chatbots be able to interact with humans in a human-like way, but they should also possess enough context awareness to incorporate the underlying business use cases. They should", he continued, "act as an elegant bridge between the needs of the end-user and the technical industry jargon and process flow of the back-end services". I like his use of the adjective "elegant", as it creates interesting contraposition between a field that is known for not being particularly elegant (IT) and the final needs of the traveler. To wrap up: chatbots may no longer be sexy, but they became elegant. And I feel that's an improvement.