How Can Revenue Managers Improve The Quality Of Their Decisions?

This article discusses how revenue managers can make better decisions by overcoming common traps and biases.

It's hard to underestimate the importance of effective, timely, and correct decisions. The revenue manager plays a crucial role in the hotel's financial success. The revenue leader is tasked with making decisions that will affect the hotel's bottom line. The quality of the decisions is of utmost importance.

What does the quality of the decisions depend on? Is being a revenue management expert sufficient to make high-quality decisions?

Recently, I came across a fantastic book by J. Edward Russo & Paul J. H. Schoemaker - "Decision traps: the ten barriers to brilliant decision-making and how to overcome them." Authors suggest that regardless of qualification and professional experience, people are subjected to biases and repeatedly make the same errors. They explore the components of these errors and detail how to rectify common decision-making mistakes. Dr. Russo and Dr. Schoemaker have improved the decision-making skills of thousands of Fortune 500 executives. Let's look at the main traps and discuss how revenue managers can avoid them.

The Traps

Plunging in

There is a common human tendency to make decisions quickly. We are almost unaware of it, but we all fall into this trap. We tend to think that we fully understand the problem and start solving it right away. Instead, we should pause and reflect. Are we solving the right issue? We also need to be specific when describing the problem rather than using generic words and terms.

For example, competitor hotel increased the weekend rate; there is a slight increase in reservations pick-up for your property, and GM is on the phone asking you to act. How many of us would just make a quick decision to increase the rate, assuming there is an uptick in market demand? How many of us will dig deeper and look at the events planned for the weekend in the city, look at the competitor hotel closer and see if it has higher occupancy because of group business and wants to sell remaining transient rooms at a higher rate? The point is that market demand might be as you originally forecasted, and an increase in rates not an optimal decision for your hotel. If we fall into the trap, we begin reacting to the incorrect situation (high market demand) versus sticking with the original pricing strategy.

Possible solutions:

- Invest time to understand the problem. Which problem are you solving? Describe it in specific terms. Is it the typical issue that requires an already established course of action to solve it, or is it a brand new challenge?

- Ask yourself if the decision is urgent and what impact it will have on the organization? By asking these questions, you will start thinking about the issue deeply and looking at it from different angles.

- Do not assume the first decision that came to mind is the best one. We are prone to take mental shortcuts and should avoid falling into this trap. Taking a step back will improve the quality of the decision.

Framing

All information is subjected to our individual perceptions. Humans look at information and then apply individual frames to interpret it. As a result, this trap leads to a selective influence of information on a person's decisions.

For example, the revenue manager received a group lead for the weekend in May and needs to recommend the discounted rate. The internal frame suggests that weekends have high transient business demand, and groups will displace the high paying guests. Because of this frame, the revenue manager will offer higher group rates, limit group rooms, suggest choosing weekdays, etc.

Framing goes hand in hand with the plunging trap. We see information, apply the frame and make a quick decision.

Possible solutions:

- Make it a habit of looking at the issue from different angles. In our example, the revenue manager could look at the group lead from another point of view - "group business is good for total revenue" and see if on this particular weekend group business will increase revenue in multiple departments (Banquets, Spa, Meeting Spaces, Rooms). Then compare it with the "transient business is the better for the weekends" point of view.

- Reframe the problem. In our example, the revenue manager could change his goal from "I need to suggest discounted rate for the group" to "I need to maximize total hotel revenue for the hotel by finding the most profitable combination of group and transient business."

- Look for alternatives. Alternatives are results of looking at the issue from different angles and correct framing. The revenue manager could propose various offers to the group: lower weekday & higher weekend group rates, lower weekend rates but higher F&B minimum and meeting spaces booking requirement, etc.

Overconfidence

Most of us place too much confidence in the quality of our information, knowledge, and experience. As a result, we neglect to collect additional information and reflect on our past decisions. We rely too much on our existing opinions and assumptions.

Possible solutions:

- Investigate the case deeply before making an important decision. Collect high-quality information and take time to analyze it. New hotel opened in the market, and occupancy of your property decreased? Do not assume these two factors have a direct correlation because "you know the market." Look at all internal and external factors that could affect your hotel's occupancy.

- Track your decisions and results. Create a simple excel spreadsheet with three columns: issue, decision, result. It will help you analyze your past decisions and make better choices in the future. You will take a more objective look at yourself, and it will help you grow professionally.

- Consult with colleagues. How did other revenue leaders approach the same issues? What GM, Director of Sales, Front Office leadership think about this new strategy? Collect as much feedback as possible from all stakeholders involved. Consider suggestions they make. It will increase your decisions' quality, and you will have a "buy-in" from the team.

Availability bias

Humans tend to base decisions on information that is recent or readily available. Information that can be easily recalled is perceived as more important. It is another mental shortcut that our minds are taking. We neglect to look for facts that require additional research.

For example, our main competitor hotel suddenly decreased the rates for the next weekend. What does it indicate, and what actions should we take? A recent example that comes to mind tells us that the competitor hotel's sudden rate reduction was a response to the last-minute group business cancelation, hence did not indicate a decrease in the overall market demand. We tend to make decisions based on this recent example. Instead, we should invest time in research - check if other properties dropped the weekend rates, call our competitor hotel, check if any flights or events were cancelled, etc. It could turn out that there was a sudden drop in market demand that we missed.

Possible solutions:

- Invest time in research.

- Gather all the facts and write them down.

- Analyse the facts to understand which ones affect the issue you need to resolve and should be considered when making a decision.

Anchoring

We like creating benchmarks and then base all decisions on them. It can be an initial piece of information we received about the situation or any value we set our minds on.

For example, March historically has the highest transient demand. The revenue manager might automatically expect that demand for coming March will be high and increase room rates. Because of this anchoring point, the revenue manager might ignore that pick-up is slower than last year (it will pick up! Demand is always high this time of the year), competitors are running sales and promotions for March (selling rooms for cheap!), etc.

Possible solutions:

- Recongnize that you have an anchor - you set your mind on a specific number, picked a favorite future scenario, or rely on convenient facts.

- Assess its quality and relevance before basing a decision on it. In our example, the revenue manager should not just expect the same level of demand and revenue that the hotel had in March for the last five years. Instead, the revenue manager should assess the current year's demand indicators and the competitors' actions. It could be that demand is lower for this coming March, and promotion is required to reach the revenue goal for the month.

Feedback and not keeping track

Another trap we fall into is not keeping track of our decisions and results. It prevents us from analyzing the result and learn from its lessons. Also, learning from the results of past decisions could be difficult because of our natural biases. People tend to attribute good results to their excellent decision-making skills and actions. At the same time, other people or unforeseen circumstances become responsible for bad outcomes. It's hard for us to look objectively at the situation. If we fail to interpret the effects of our decisions objectively, we won't improve our decision-making skills.

Possible solutions:

- Write down the decision and its results.

- Explain how you see the connection between decision and results.

- Ask for feedback from colleagues.

- Summarize points of view and detail what was good and bad in the decision you made.

- List actions you will take to improve your future decisions.

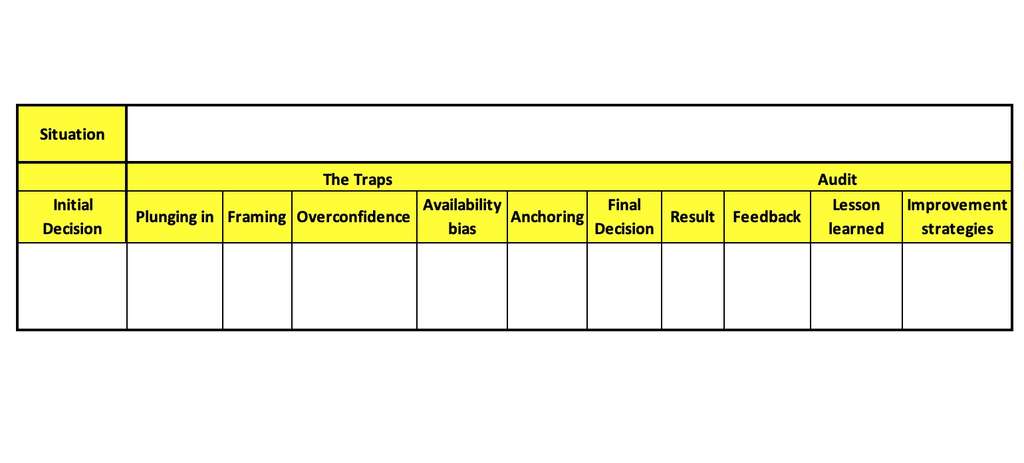

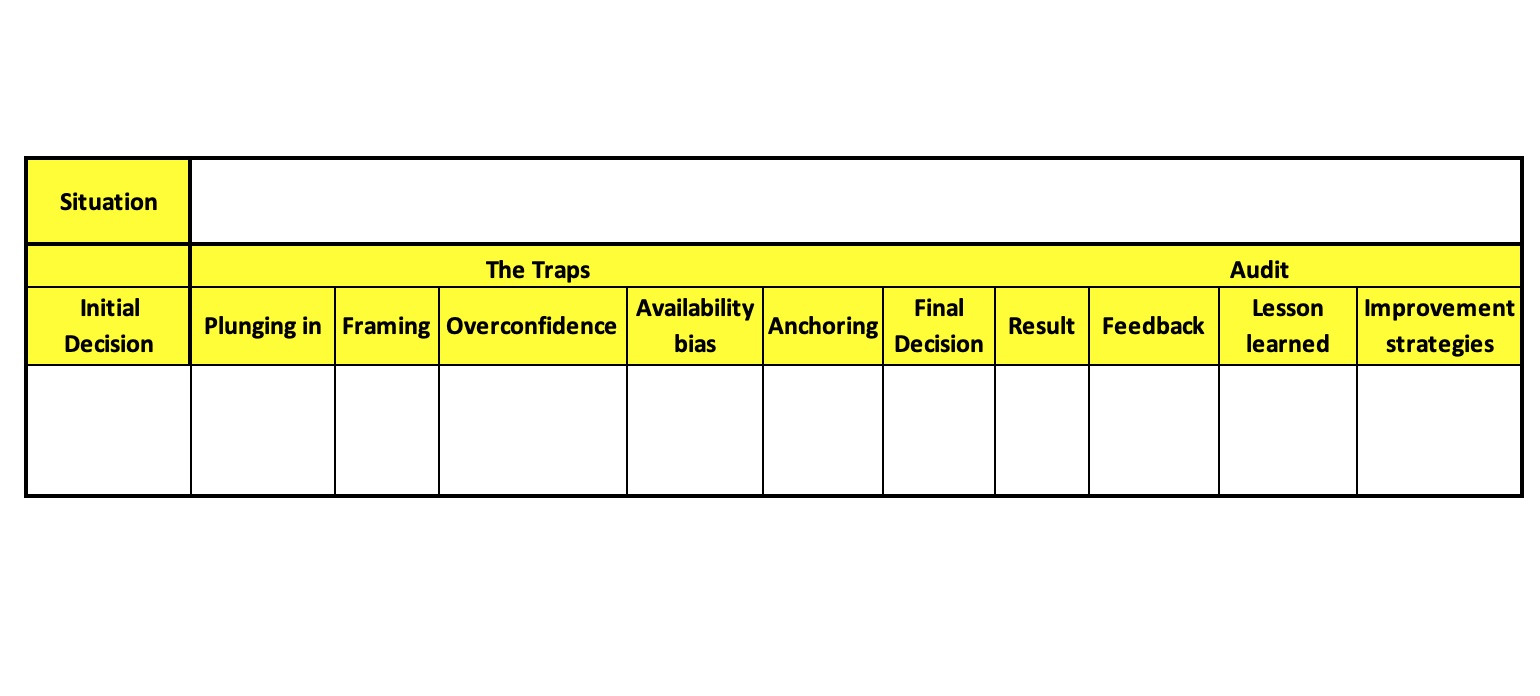

Failure to audit your decision process

If we fail to create an organized approach to understanding our own decision-making, we will continue falling into all the above traps. Establish a decision-audit process. List initial decision, address all biases and traps, and list the final decision. When results are available, analyze them, and detail lesson learned and improvement strategies.

When will I find the time to go through this process? I am busy with all my tasks already.

A reasonable question, right?

It's an investment that will require effort at the beginning and will pay off in the future. Improving the quality of your decisions will save you time dealing with the consequences of bad decisions. You will free up time to tackle new challenges. Going through a decision-process audit is like training muscles - the more you do it, the stronger you become. Eventually, it will be part of your routine and will take less and less time.