Post hangover: What is the right price for Bordeaux en primeur 2023?

No two years are alike in the fine wine market, especially in Bordeaux. The 2022 vintage was of outstanding quality and its release in the spring of 2023 followed several years of rising prices. Since then, the market has taken a turn for the worse: sluggish demand combined with significant inventories have sent prices into a downward spiral. In this context, the pricing of the 2023 Bordeaux en primeur wines is being watched closely. For the châteaux, setting the right price is a real balancing act. Collectively, they are aware that the market needs 2023s to sell well, but they also want to avoid devaluing previous vintages by comparison. Individually, many châteaux are anxious not to squander the marketing efforts of recent years and fear diluting their brand by positioning themselves inappropriately.

If the commodity is scarce, the price is raised, but if the quantity is more than is sufficient to supply the demand, the price falls. Adam Smith

How to determine a fair price?

To determine the fair price for each wine, we use a model based on a simple principle: the price of the latest vintage must be consistent with the vintages already on the market and still available for sale1.

Intuitively, each time a new vintage comes on the market, it is “surrounded” by its predecessors, which can serve as points of comparison to help determine an appropriate price for the wines to be sold en primeur. Of course, it is never possible to find perfectly similar wines due to differences in quality, age and/or reputation. It is therefore necessary to use statistical tools to take these differences into account and estimate a point of comparison that is as relevant as possible – to help determine the right price at which a wine should be released on the market.

Presentation of the model

In concrete terms, for the 2023 vintage, which is released in the spring of 2024, the approach works as follows:

Step 1: wines from vintages 2005 to 2022 that are already traded on the market are analyzed, using regressions, to infer the following elements: the value associated with each château's individual reputation (= château effect), the relationship between quality and price (= quality effect), and the relationship between age and price (= age effect).

- To ensure a relevant framework for comparison, we use price data from the Négoce (i.e., Bordeaux wine trade) – since it is the Négoce that is responsible for providing the link between châteaux and wine merchants worldwide during the en primeur campaign.

- Our analysis covers 74 châteaux for which we had access to all the necessary information. This sample is representative, as it contains the majority of the “big names” in Bordeaux. Only a few Pomerol wines are missing, for which it is difficult to obtain data.

- Three sources of information are used to estimate quality. First, we consider Wine Expert Rating (WxR) scores, which statistically aggregate the scores of multiple experts to estimate the true (unobserved) quality of wines. The WxR approach reduces the bias introduced by the preferences that experts may have for particular styles of wine. We also include scores from The Wine Advocate (TWA), which, despite the retirement of Robert Parker, remains an important reference that can influence buyers. Finally, we use Saturnalia (SAT) scores, which are based on artificial intelligence analysis of meteorological and satellite data. SAT is the most objective measure of quality, but it can only take into account the situation at harvest time and not the work done in the cellar. Nor can it take into account decisions such as sorting and/or downgrading part of the harvest if the quality is not fully satisfactory. These reasons justify our decision to use SAT only to analyze the quality of the vintage as a whole, and not to model the price of individual wines.

- We use standardized scores: the original score is reduced by the average score over the sample and then divided by the standard deviation of the scores. This makes scores from different sources and experts comparable. A standardized score of 0.00 means that a wine received a score perfectly in line with the average.

- We also take into account two phenomena that can affect prices. First, wines with scores close to 100 points can sell at much higher prices than others, due to the value some consumers place on a potentially “perfect” wine. In addition, clientele effects can alter the average price level of different vintages. In Bordeaux, it is often said that great vintages attract a different clientele. This may affect the price level of wines in such vintages. We therefore include a variable to control for any effect associated with an outstanding vintage in our model.

- For the most prestigious wines, status is the determining factor, and expert ratings often play a lesser role. Our analysis therefore distinguishes the First Classified Growths and alike, as well as their second wines2, from the other Bordeaux Crus.

Step 2: we use the effects estimated in the first step to estimate the fair release price. For each wine, we add the château effect, and the quality effect multiplied by the score obtained for the last vintage.

- Age doesn't enter the model directly, since wines sold en primeur have an age of zero. Indirectly, however, age plays a role as older wines are more expensive. In other words, the age effect implies a discount for the most recent vintage brought to market. The size of this discount depends largely on market conditions. For example, in 2011, when the 2010 vintage was released, the age effect was zero. It was an exceptional period characterized by low interest rates and an incredible appetite for Bordeaux wines, especially from new consumer countries and speculators. Today, conditions are very different and the age effect is back: buyers expect a discount when they buy en primeur.

- At this point, it's worth revisiting one of the debates that fueled the marketing of the 2022 vintage a year ago, which concerned the impact of inflation and interest rates. Many châteaux argued that high inflation justified higher prices. We already suggested last year that this mechanism was flawed (see this article). In fact, the opposite is more likely the case. High interest rates mean that it's expensive to tie up money today to buy wines that aren't yet available. It only makes sense to do so if one saves on price. On the other hand, inflation has a negative effect on capital markets and thus on the financial situation of those who can afford to buy fine wines. In other words, inflation and high interest rates are likely to put downward pressure on fine wine prices.

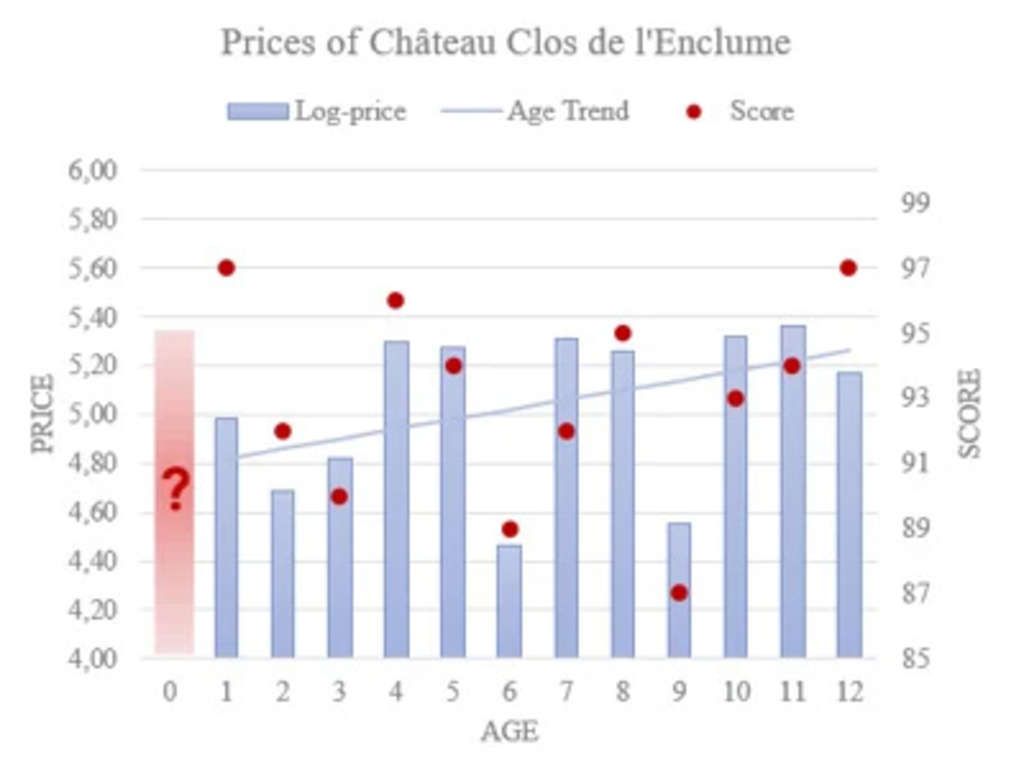

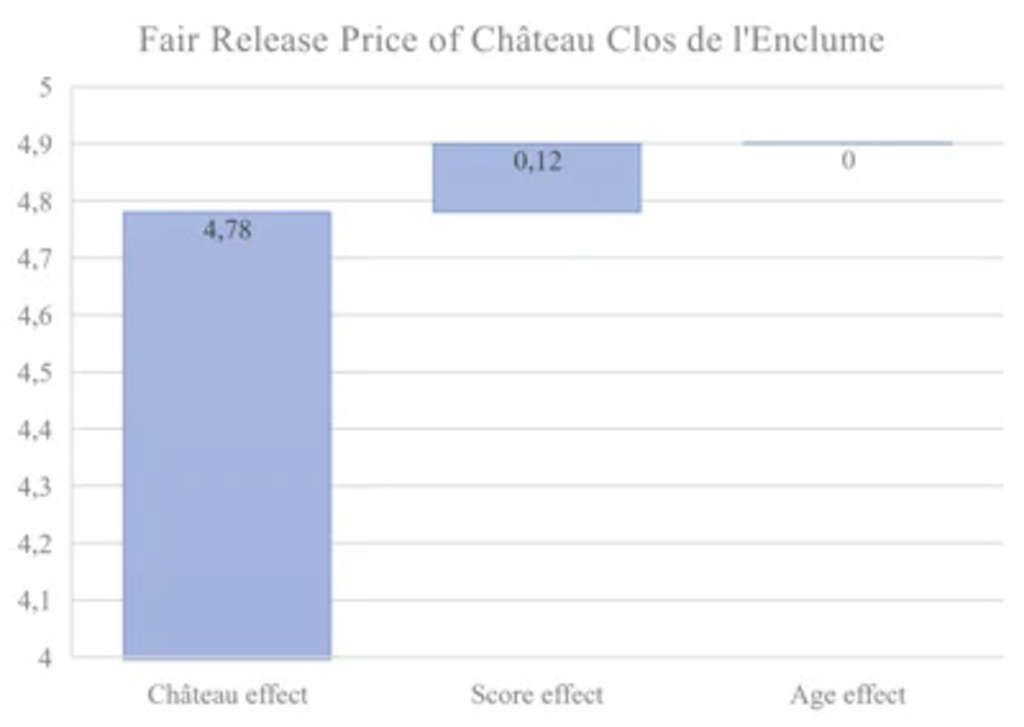

Exhibit 1 uses an example to illustrate the approach outlined above. Specifically, for the price of a wine from vintage 2023 to be considered reasonable, it must reflect the current reputation of the chateau producing it and take into account the quality of the wine in that vintage and its age (which, unlike wines already on the market, is zero). If the price is right, a potential buyer should be indifferent between buying a 2023 wine and a comparable wine from an earlier vintage. The term "comparable" is used deliberately: the goal is not to find wines that are completely identical – that's impossible. Rather, it is a matter of identifying wines that, by virtue of their characteristics, have qualities of equal importance that compensate for their shortcomings relative to other wines.

Exhibit 1: Presentation of the approach used to estimate the fair exit price

Step 1: prices of vintages already trading on the secondary wine market are analyzed in order to estimate the typical price level of Château Clos de l'Enclume (i.e., the price at zero age and score equal to the sample average) (= Château effect), the relationship between quality and price (= quality effect), and the relationship between age and price (= age effect).

Note: The natural logarithm of price is used for analysis.

Step 2: The fair price of the latest vintage can be estimated by adding together the Château effect and the quality effect (taking into account the score obtained by the wine in the corresponding vintage). Age does not contribute to price, unlike for previous vintages. In other words, zero age implies a discount for the latest vintage relative to older vintages.

What about the quality of the 2023 vintage?

Most experts have published their reports about the 2023 vintage. As usual, comparisons between 2023 and previous vintages are common. Some suggest that 2023 resembles 2001, 2012 or 2014, which are good vintages, while others go as far as comparing it to the excellent 1990 vintage. Hardly anyone is putting 2023 on equal footing with the exceptional 2022 and 2016 vintages. Yet many wines score high and get rave reviews. The most enthusiastic experts are James Suckling (who regularly gives the most generous scores), Jeff Leve and Jane Anson. One word that comes up a lot is "heterogeneity"3. It's probably the best way to describe this vintage. Saturnalia, which uses only meteorological and satellite data, places 2023 above 2013, close to 2014, 2017, and 2021, but well behind 2016, 2019, and 2022.

Overall, it seems appropriate to consider 2023 as a good to very good vintage, marked by substantial variations in quality, with some châteaux producing great wines and other.

Reputation, quality, and age effects

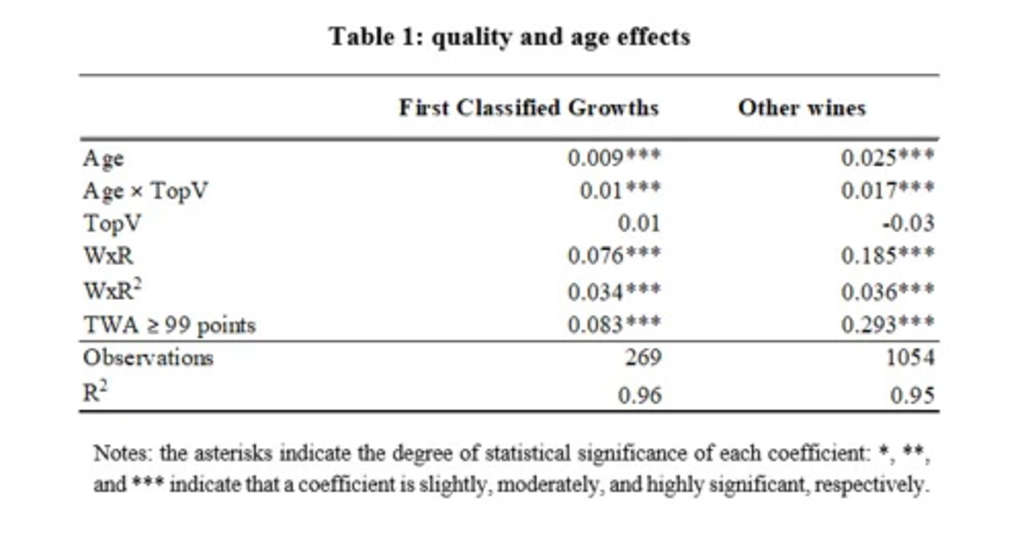

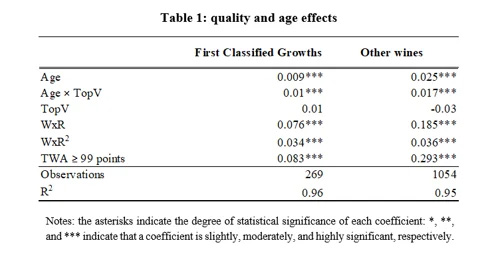

Table 1 shows how age and score affect the prices of wines from vintages prior to 2023. The coefficients reported in the table are the result of the regression estimation presented in step 1 above. The asterisks next to the coefficients indicate the variables with the largest impact on prices: the presence of *, ** or *** indicates a coefficient that is slightly, moderately or highly statistically significant, respectively. The absence of an asterisk indicates that the coefficient is not significant and that the variable in question therefore has a negligible impact on prices. The number of observations used to estimate each regression and the R-squared (which assesses the overall quality of the estimation) are also reported. The R-squares of both regressions are close to 1.00, indicating that the model has very strong explanatory power (conversely, a value close to 0.00 would indicate that the model is not relevant).

Effect of the quality of the vintage as a whole: The variable denoted TopV captures any price difference between a wine from an exceptional vintage (“top”) and a strictly similar (same age, same score) wine from a non-exceptional vintage. There is no significant difference between exceptional and non-exceptional vintages. This can be explained by two complementary phenomena. First, it should be noted that quality is already taken into account by the scores of the individual wines. The associated coefficients are significantly positive (see below for a detailed discussion). This means that wines in exceptional vintages are indeed more expensive because they receive higher scores, but the fact that the vintage is exceptional does not in itself lead to an additional price premium. Probably the proliferation of great vintages combined with the disappearance of genuinely weak vintages also contributes to this result. Overall, this potentially calls into question Bordeaux’s practice of valuing great vintages differently from others when they are released. In general, this has however little impact on the price estimate for the 2023 vintage, which does not seem to belong to the category of great vintages.

Effect of the quality of the individual wines: Only WxR scores correlate significantly with prices. TWA scores seem to have no effect on prices, except when they are equal to 99 or 100 points. The few affected wines sell for about 8% more (First Classified Growths) to 30% more (other wines). This suggests that the market is still interested in wines that are deemed near perfect according to TWA. The WxR effect is both linear and quadratic, meaning that wines with particularly high scores sell for significantly more than others. The quality effect is much weaker for the First Classified Growths. This is due to the fact that these wines are valued mainly for their prestige; moreover, their scores are expected to be high – so a very good score has a limited effect because exceptional quality is expected.

Effect of age: Age has a moderate effect on prices. This effect is less significant for First Classified Growths, for which it translates into a price increase of about 1% (average to excellent quality vintage) to 2% (exceptional quality vintage) per additional year in cellar. For other wines, the effect is about 2.5% to 4% per year of cellaring. This effect accumulates over time, resulting in significant premiums for wines that are 10 years old or more. In the context of en primeur wines, age has a negative influence. This is logical: buying and storing bottles is expensive, so a young wine must be sold at a lower price than an equivalent older wine. In the context of this study, these observations suggest that, for the same quality, 2023 prices should be around 2% (First Classified Growths) to 5% (other wines) lower than those of 2021s already on the market.

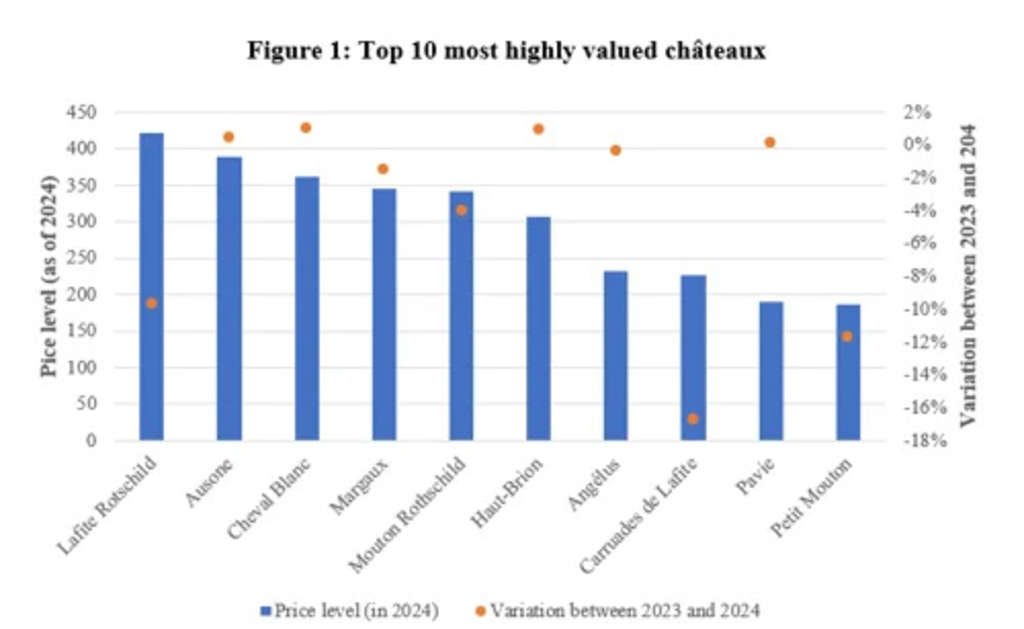

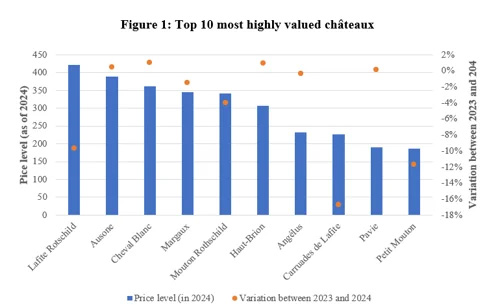

Figure 1 shows the 10 strongest brands in our sample. This figure plots the price level of these wines, assuming that their score is equal to the average of the entire sample and that their age is zero. It also shows the price change since last year. As mentioned above, several famous Pomerol châteaux are not included in the analysis due to a lack of sufficiently complete and accurate data.

The top 10 includes only First Classified Growths and their second wines. At first glance, it may seem surprising that Carruades de Lafite or even Petit Mouton rank higher than wines like Palmer or Léoville Las Cases, but this is because the values in the chart reflect only the effect of each wine's individual reputation, regardless of quality. Carruades de Lafite and Petit Mouton often have scores close to the average, but Palmer and Léoville Las Cases usually have much higher scores, allowing them to sell their wines at higher prices than those shown in Figure 2. We can also see that most of the major brands have fallen since last year, by an average of just over 4%. Liv-ex has fallen by around 15% over the same period. This discrepancy is explained by the fact that our data corresponds to the prices at which négociants would like to sell, while Liv-ex's data corresponds to the prices at which transactions actually take place on their platform. This leads to two phenomena: (1) our prices are likely to be overestimated by a few percent (ask prices are by definition always higher than market prices), and (2) their dynamics are likely to be smoothed, as both négociants and merchants are slow to adjust their prices to market trends.

Our data remains representative as it reflects much larger trading volumes than those recorded on the Liv-ex platform, but in the current context it probably leads to an overestimation of market prices by 5% to 10%.

Estimated prices of Bordeaux 2023 wines

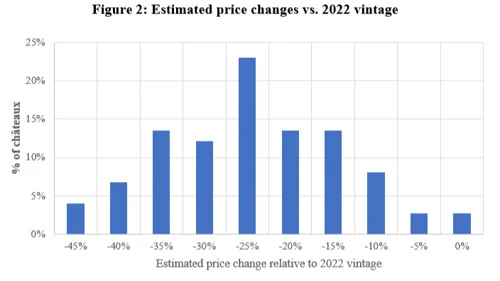

The model suggests significant price reductions compared to the 2022 vintage. On average, prices would have to fall by 26% for the 2023 vintage to be valued in line with the vintages currently traded on the secondary market. Figure 2 shows that the situation varies greatly from château to château. A small minority (6%) can afford to keep prices more or less stable (5% decrease or less). The vast majority of châteaux will, however, have to reduce their prices by between 20% and 30%. However, 24% of the châteaux are expected to reduce their prices even more drastically.

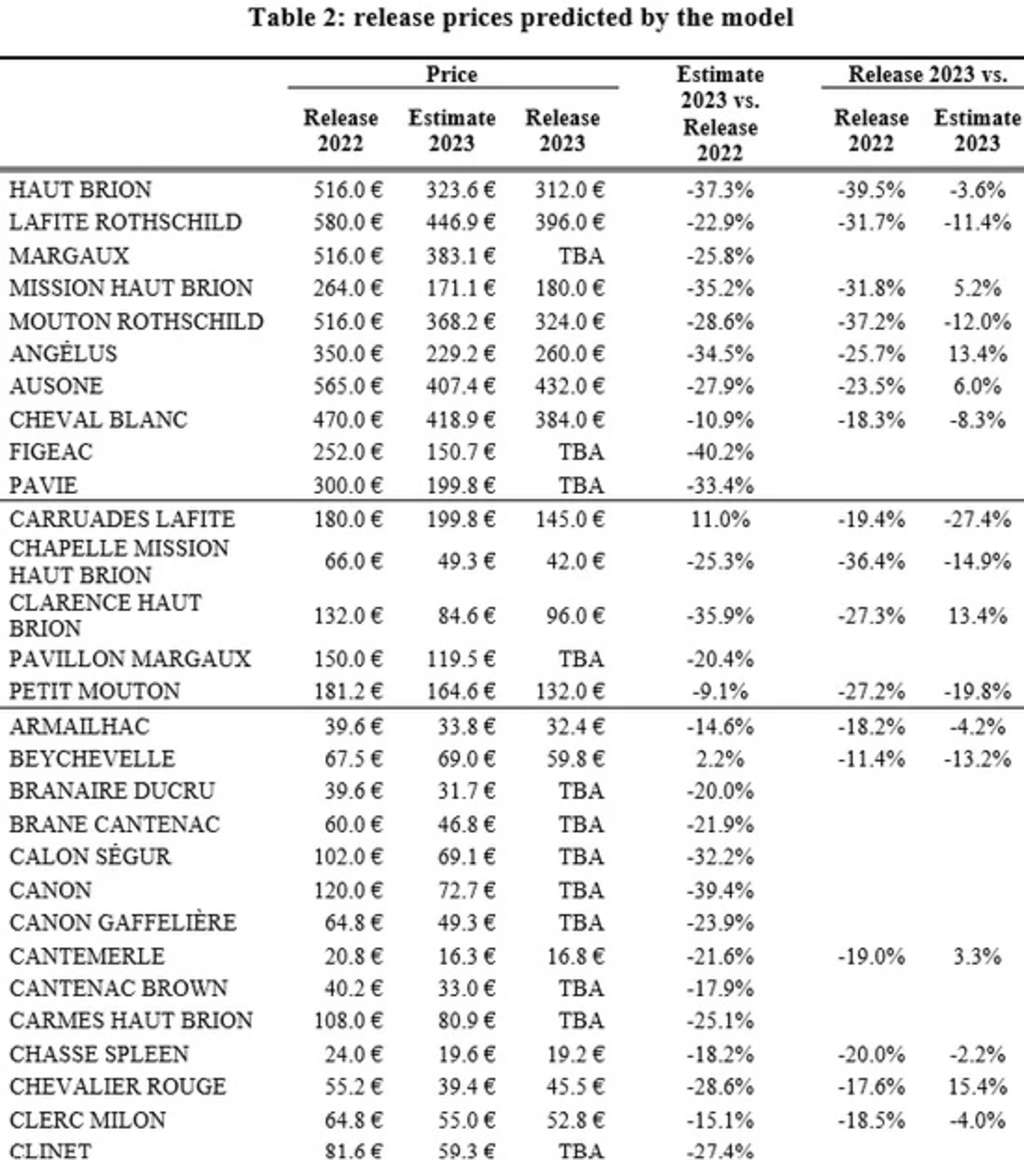

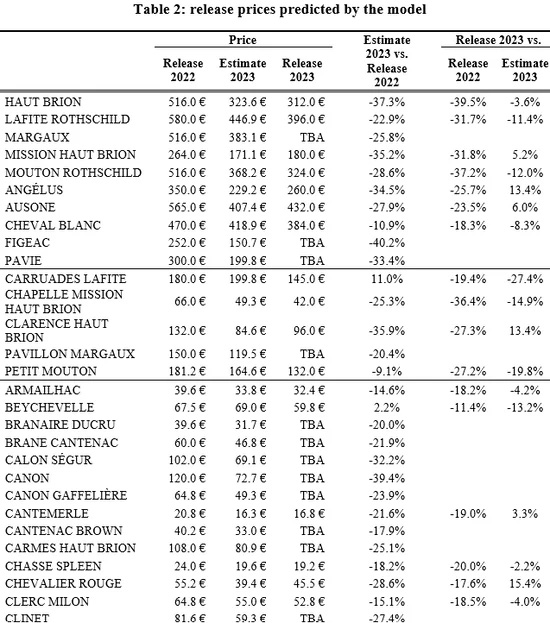

Table 2 shows the projected release prices for each wine in our sample. These are ex-négoce prices, so a margin of approximately 17% and VAT must be added to obtain an estimate of the final consumer price. The table also compares these estimates with prices for the same wines in the 2022 vintage and the actual release price for wines already on the market at the time of writing.

The prices of the wines already released fell by 23.9% compared to the 2022 vintage. The correlation between the price changes predicted by the model and those observed is 0.66. In other words, the majority of châteaux have so far behaved in line with the model's predictions. Interestingly, the wines that decreased their prices the most are not necessarily those that appear to be the most attractively valued according to the model. On the contrary, wines such as Léoville Las Cases and l'Evangile, which reduced their prices by 40% and 30% respectively, appear to be between 25% and 30% overpriced relative to the model. This may seem surprising, but it is explained by the fact that these châteaux were among those that deviated the most from what the model predicted as a fair price last year. In other words, they were far too expensive, and the price adjustments made for the 2023 vintage are not sufficient to fully correct this situation.

Certain wines seem to be cheaper than the model predicts: Lafite Rothschild, Mouton Rothschild, and even more so their second wines, Carruades and Petit Mouton. Surprisingly, unlike in previous years, these wines are not sold out on the wine merchants' websites. This is probably due to the fact that, as mentioned above, we use price data that tends to adjust slowly, which in a bear market tends to overestimate fair release prices. Market volume may also play a role. Overall, it seems prudent to assume that the estimates provided by the model represent upper bounds of fair prices in the current context.

Accuracy of the model

We have already used a very similar model to estimate the fair release price of wines from the 2022 vintage. This provides us with a point of comparison to assess the model's ability to give relevant indications consistent with market dynamics.

Specifically, we can compare the differences between the release prices estimated by our model for wines from the 2022 vintage and those actually observed with (i) the evolution of the prices of these wines since their release (i.e., over 12 months) and (ii) the effective demand for those wines. To estimate (ii), we analyze data from the Cellar Tracker (CT) website, covering vintages from 2005 to 2022. CT is the world leader in online cellar management, allowing users to list the wines they have in their cellar, along with the corresponding quantities. In particular, you can see the quantity of each wine and vintage owned by the CT community, giving you a relatively accurate idea of the actual demand for a wine. For example, all CT users currently (i.e. in May 2024) have a total of over 40,000 bottles of Pontet Canet 2009 in their cellars. This represents more than 10% of the total production of this wine in this vintage. CT data can therefore be considered representative of market demand.

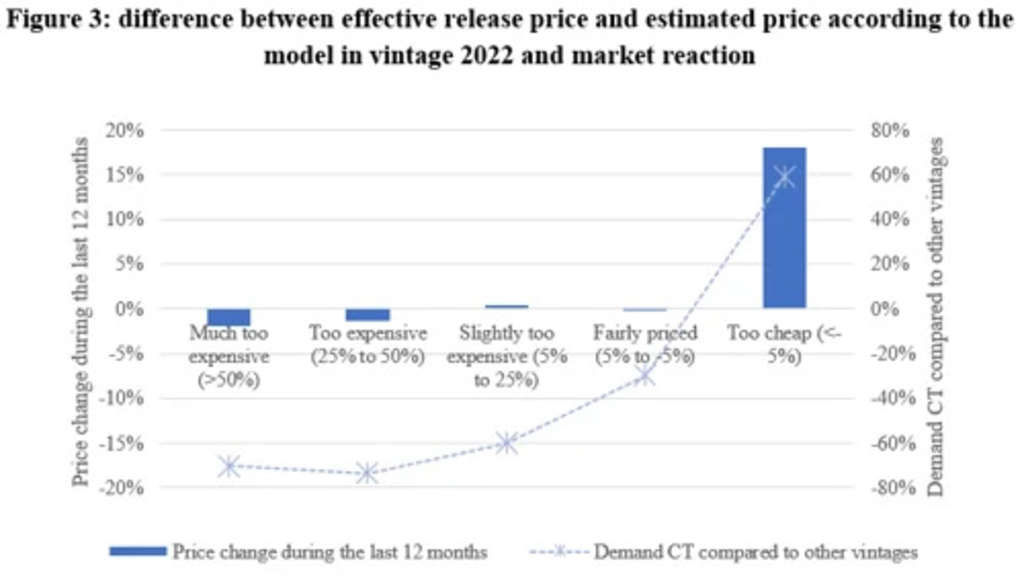

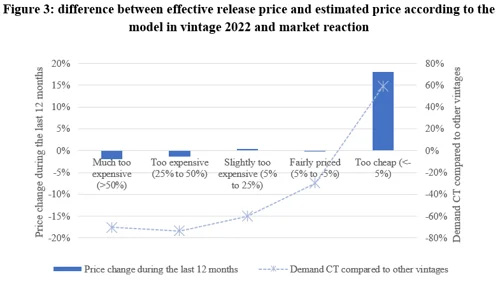

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the difference between the actual release price and the price estimated by the model for the 2022 vintage and the subsequent market reaction. The 2022 Bordeaux wines are ranked into five categories according to the difference between their actual release price and the price estimated by the model. The category on the far left corresponds to wines whose price was much higher than the model’s estimate (more than 50% difference), while those on the far right are those that were at least 5% cheaper than the model’s estimate. The bars (left scale) show how prices in each category changed over 12 months. Few wines were too cheap, but these are the only ones that have increased since last year. The dots (right scale) show the volume of wine purchased by the CT community, relative to what would have been expected given the purchasing behavior of previous vintages. Consistent with the previous observation, we can see that the few underpriced wines benefited from sustained demand; in fact, these were the only wines that sold better to the CT community than in previous vintages. For the other wines, there is a clear link between an excessive release price and subsequent unfavorable price and demand dynamics. Again, it is interesting to note that prices adjust more easily upwards than downwards. This suggests that wines identified as overpriced are likely to continue to stagnate or even decline in the coming years.

Summary

Our analysis suggests that fair prices for 2023 Bordeaux should be on average 25% to 30% below those of the 2022 vintage. It should be noted that “fair price” is not synonymous with “bargain”. It's simply a fair price based on the various information and variables available to us at the time of this analysis. As explained above, in the current context, it is likely that the estimate provided by our model reflects a ceiling price. For châteaux that wish to sell their wines easily, a downward adjustment of 5% to 10% on this estimate seems appropriate. In other words, equilibrium prices for the 2023 vintage are likely to be around -35% on average relative to the release prices for 2022 Bordeaux.

Conclusion

After a great 2022 vintage, Bordeaux is waking up with a hangover. Last year, there was an opportunity to rebuild positive momentum, and the 2022 campaign could have been a considerable success. However, excessive prices diverted demand, and sales ultimately proved disappointing. After a 2021 vintage that was also overpriced, the entire Bordeaux value chain finds itself with significant inventories. The 2023 vintage is less well-born overall, but still seems to be full of very good wines, and even some truly great ones. Its main problem is therefore not a lack of quality, but a context that makes setting a fair release price a very complicated and vitally important exercise. The 2023s have to sell, but many Châteaux feel that it is important not to “kill the market” for earlier vintages by setting prices too low.

The truth is that, in the current context, the long-term counts for little for the majority of industry players and buyers. Fair prices may not be enough. Ideally, truly attractive prices would be needed to sell significant volumes. From a long-term perspective, it would probably be better to ensure that 2023 is a vintage that is widely sold and unavailable at the initial release prices, rather than one that remains 20% cheaper than 2022 for a long period and doesn't sell.

References

1. Readers interested in a more detailed view of the model are invited to consult the following article: Masset, P., Weiskopf, J., & Cardebat, J. (2023). Efficient pricing of Bordeaux en primeur wines. Journal of Wine Economics, 18(1): 39-65.

2. We consider as “First Growth alike” the three Saint-Emilion wines that were classified as First Growth A until 2022 and have since decided to leave the classification system (Ausone, Cheval Blanc and Angélus), as well as Mission Haut-Brion, which is unclassified but receives similar ratings to its neighbor Haut-Brion (which is a First Classified Growth).

3. For instance, N. Martin notes that “nobody will deny that, unlike 2022, 2023 is a heterogeneous vintage.” (vinous.com/articles/the-dalmatian-vintage-bordeaux-2023-apr-2024)

EHL Hospitality Business School

Communications Department

+41 21 785 1354

EHL